A Dive into Vision-Language Models

Human learning is inherently multi-modal as jointly leveraging multiple senses helps us understand and analyze new information better. Unsurprisingly, recent advances in multi-modal learning take inspiration from the effectiveness of this process to create models that can process and link information using various modalities such as image, video, text, audio, body gestures, facial expressions, and physiological signals.

Since 2021, we’ve seen an increased interest in models that combine vision and language modalities (also called joint vision-language models), such as OpenAI’s CLIP. Joint vision-language models have shown particularly impressive capabilities in very challenging tasks such as image captioning, text-guided image generation and manipulation, and visual question-answering. This field continues to evolve, and so does its effectiveness in improving zero-shot generalization leading to various practical use cases.

In this blog post, we'll introduce joint vision-language models focusing on how they're trained. We'll also show how you can leverage 🤗 Transformers to experiment with the latest advances in this domain.

Table of contents

- Introduction

- Learning Strategies

- Datasets

- Supporting Vision-Language Models in 🤗 Transformers

- Emerging Areas of Research

- Conclusion

Introduction

What does it mean to call a model a “vision-language” model? A model that combines both the vision and language modalities? But what exactly does that mean?

One characteristic that helps define these models is their ability to process both images (vision) and natural language text (language). This process depends on the inputs, outputs, and the task these models are asked to perform.

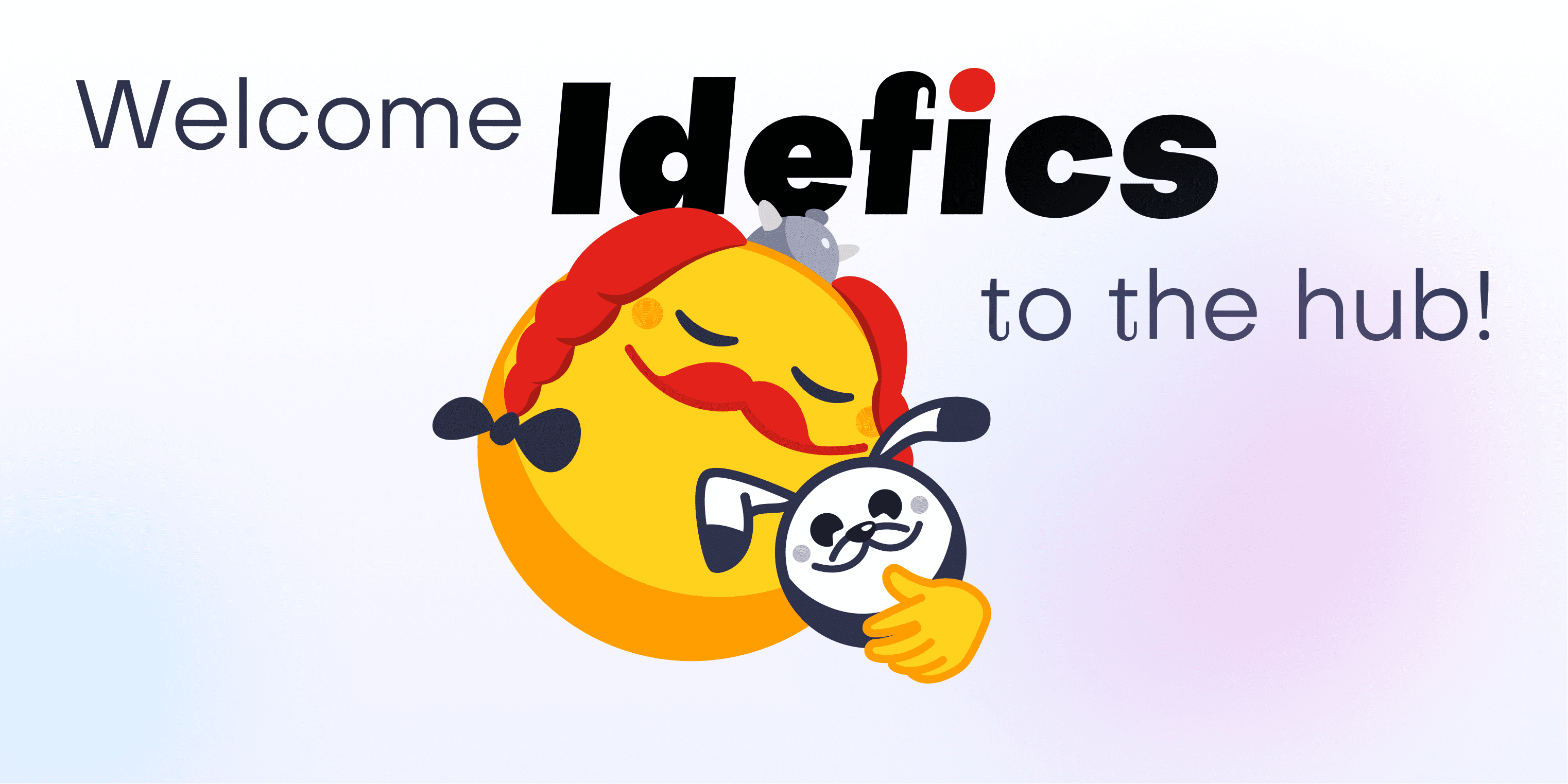

Take, for example, the task of zero-shot image classification. We’ll pass an image and a few prompts like so to obtain the most probable prompt for the input image.

The cat and dog image has been taken from here.

To predict something like that, the model needs to understand both the input image and the text prompts. The model would have separate or fused encoders for vision and language to achieve this understanding.

But these inputs and outputs can take several forms. Below we give some examples:

- Image retrieval from natural language text.

- Phrase grounding, i.e., performing object detection from an input image and natural language phrase (example: A young person swings a bat).

- Visual question answering, i.e., finding answers from an input image and a question in natural language.

- Generate a caption for a given image. This can also take the form of conditional text generation, where you'd start with a natural language prompt and an image.

- Detection of hate speech from social media content involving both images and text modalities.

Learning Strategies

A vision-language model typically consists of 3 key elements: an image encoder, a text encoder, and a strategy to fuse information from the two encoders. These key elements are tightly coupled together as the loss functions are designed around both the model architecture and the learning strategy. While vision-language model research is hardly a new research area, the design of such models has changed tremendously over the years. Whereas earlier research adopted hand-crafted image descriptors and pre-trained word vectors or the frequency-based TF-IDF features, the latest research predominantly adopts image and text encoders with transformer architectures to separately or jointly learn image and text features. These models are pre-trained with strategic pre-training objectives that enable various downstream tasks.

In this section, we'll discuss some of the typical pre-training objectives and strategies for vision-language models that have been shown to perform well regarding their transfer performance. We'll also touch upon additional interesting things that are either specific to these objectives or can be used as general components for pre-training.

We’ll cover the following themes in the pre-training objectives:

- Contrastive Learning: Aligning images and texts to a joint feature space in a contrastive manner

- PrefixLM: Jointly learning image and text embeddings by using images as a prefix to a language model

- Multi-modal Fusing with Cross Attention: Fusing visual information into layers of a language model with a cross-attention mechanism

- MLM / ITM: Aligning parts of images with text with masked-language modeling and image-text matching objectives

- No Training: Using stand-alone vision and language models via iterative optimization

Note that this section is a non-exhaustive list, and there are various other approaches, as well as hybrid strategies such as Unified-IO. For a more comprehensive review of multi-modal models, refer to this work.

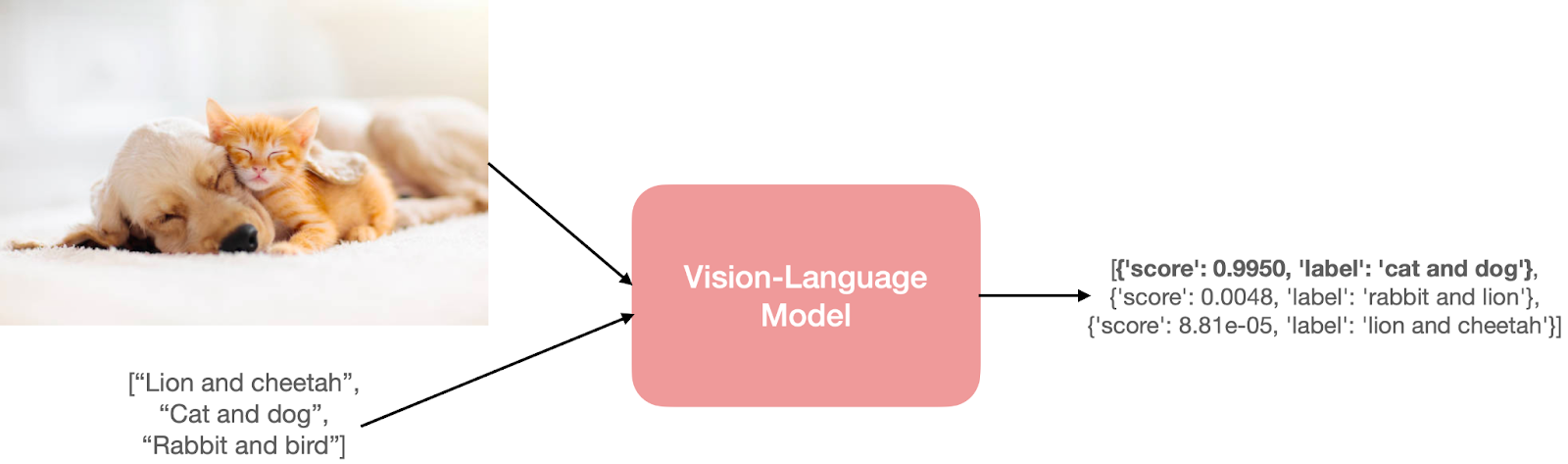

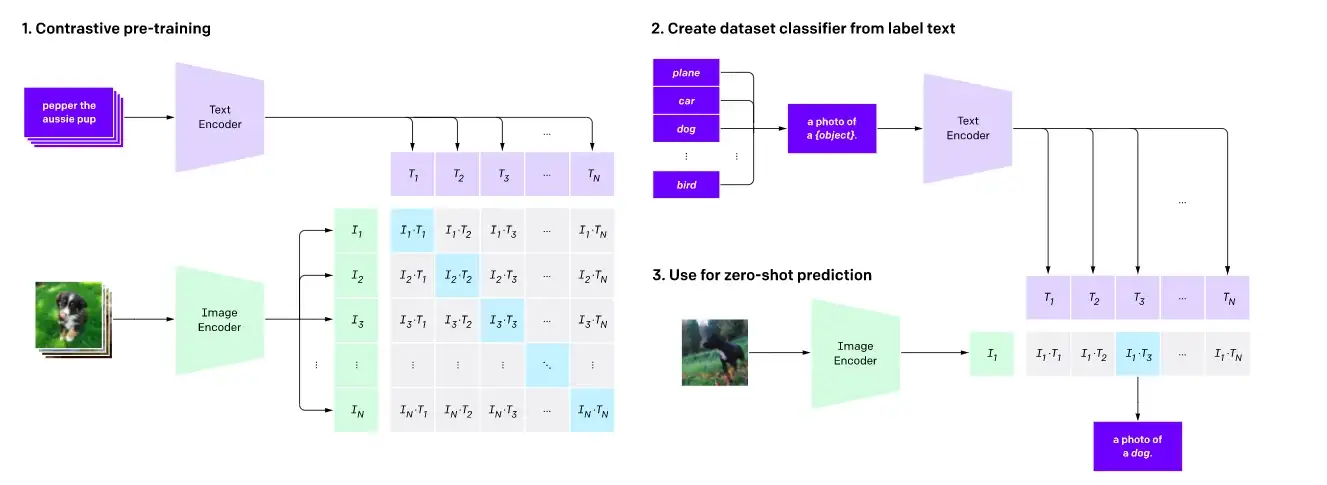

1) Contrastive Learning

Contrastive pre-training and zero-shot image classification as shown here.

Contrastive learning is a commonly used pre-training objective for vision models and has proven to be a highly effective pre-training objective for vision-language models as well. Recent works such as CLIP, CLOOB, ALIGN, and DeCLIP bridge the vision and language modalities by learning a text encoder and an image encoder jointly with a contrastive loss, using large datasets consisting of {image, caption} pairs. Contrastive learning aims to map input images and texts to the same feature space such that the distance between the embeddings of image-text pairs is minimized if they match or maximized if they don’t.

For CLIP, the distance is simply the cosine distance between the text and image embeddings, whereas models such as ALIGN and DeCLIP design their own distance metrics to account for noisy datasets.

Another work, LiT, introduces a simple method for fine-tuning the text encoder using the CLIP pre-training objective while keeping the image encoder frozen. The authors interpret this idea as a way to teach the text encoder to better read image embeddings from the image encoder. This approach has been shown to be effective and is more sample efficient than CLIP. Other works, such as FLAVA, use a combination of contrastive learning and other pretraining strategies to align vision and language embeddings.

2) PrefixLM

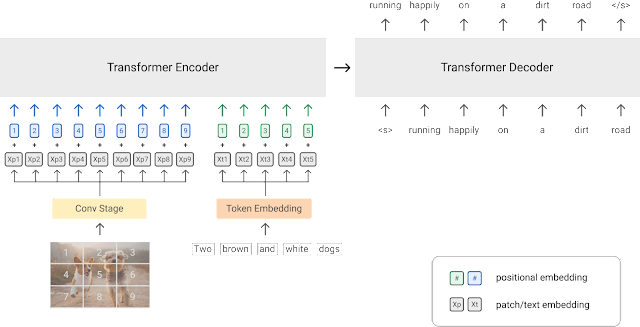

A diagram of the PrefixLM pre-training strategy (image source)

Another approach to training vision-language models is using a PrefixLM objective. Models such as SimVLM and VirTex use this pre-training objective and feature a unified multi-modal architecture consisting of a transformer encoder and transformer decoder, similar to that of an autoregressive language model.

Let’s break this down and see how this works. Language models with a prefix objective predict the next token given an input text as the prefix. For example, given the sequence “A man is standing at the corner”, we can use “A man is standing at the” as the prefix and train the model with the objective of predicting the next token - “corner” or another plausible continuation of the prefix.

Visual transformers (ViT) apply the same concept of the prefix to images by dividing each image into a number of patches and sequentially feeding these patches to the model as inputs. Leveraging this idea, SimVLM features an architecture where the encoder receives a concatenated image patch sequence and prefix text sequence as the prefix input, and the decoder then predicts the continuation of the textual sequence. The diagram above depicts this idea. The SimVLM model is first pre-trained on a text dataset without image patches present in the prefix and then on an aligned image-text dataset. These models are used for image-conditioned text generation/captioning and VQA tasks.

Models that leverage a unified multi-modal architecture to fuse visual information into a language model (LM) for image-guided tasks show impressive capabilities. However, models that solely use the PrefixLM strategy can be limited in terms of application areas as they are mainly designed for image captioning or visual question-answering downstream tasks. For example, given an image of a group of people, we can query the image to write a description of the image (e.g., “A group of people is standing together in front of a building and smiling”) or query it with questions that require visual reasoning: “How many people are wearing red t-shirts?”. On the other hand, models that learn multi-modal representations or adopt hybrid approaches can be adapted for various other downstream tasks, such as object detection and image segmentation.

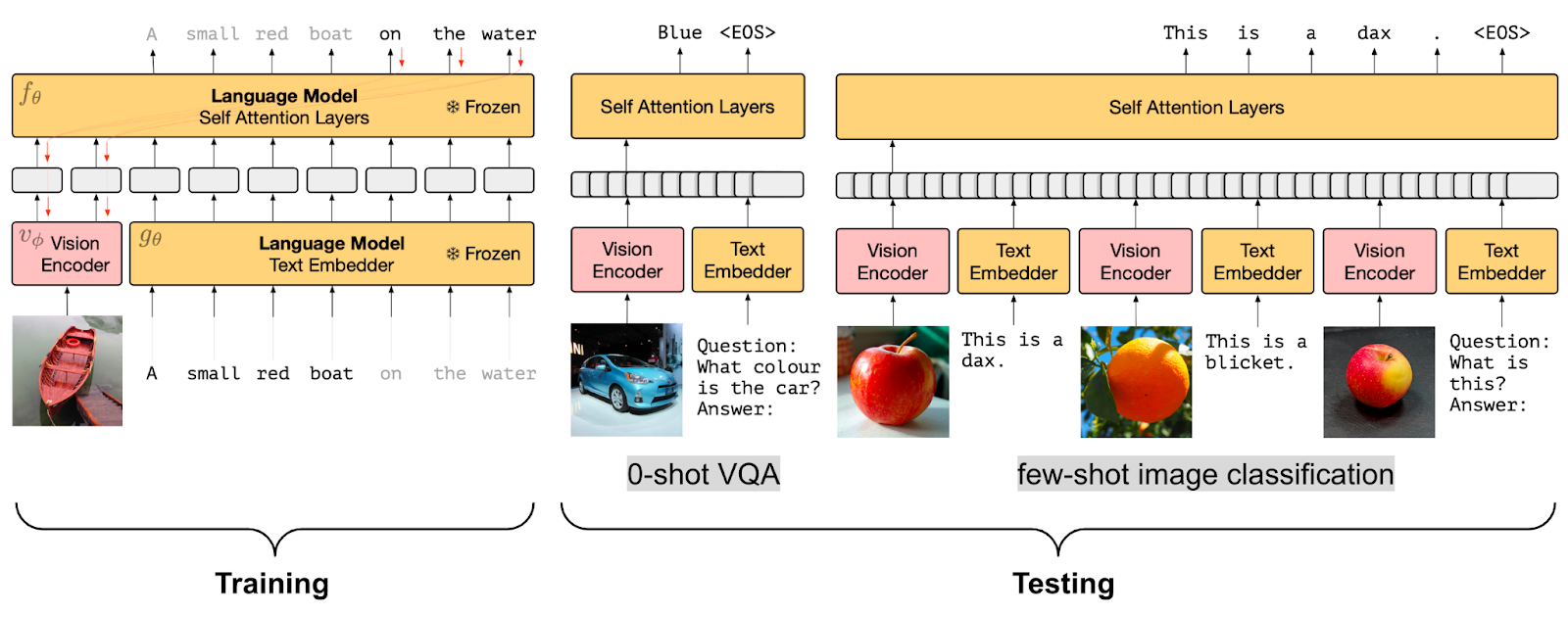

Frozen PrefixLM

Frozen PrefixLM pre-training strategy (image source)

While fusing visual information into a language model is highly effective, being able to use a pre-trained language model (LM) without the need for fine-tuning would be much more efficient. Hence, another pre-training objective in vision-language models is learning image embeddings that are aligned with a frozen language model.

Models such as Frozen and ClipCap use this Frozen PrefixLM pre-training objective. They only update the parameters of the image encoder during training to generate image embeddings that can be used as a prefix to the pre-trained, frozen language model in a similar fashion to the PrefixLM objective discussed above. Both Frozen and ClipCap are trained on aligned image-text (caption) datasets with the objective of generating the next token in the caption, given the image embeddings and the prefix text.

Finally, models such as MAPL and Flamingo keep both the pre-trained vision encoder and language model frozen. Flamingo sets a new state-of-the-art in few-shot learning on a wide range of open-ended vision and language tasks by adding Perceiver Resampler modules on top of the pre-trained frozen vision model and inserting new cross-attention layers between existing pre-trained and frozen LM layers to condition the LM on visual data.

A nifty advantage of the Frozen PrefixLM pre-training objective is it enables training with limited aligned image-text data, which is particularly useful for domains where aligned multi-modal datasets are not available.

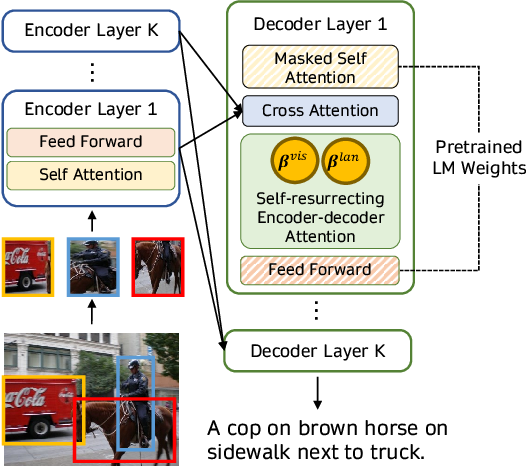

3) Multi-modal Fusing with Cross Attention

Fusing visual information with a cross-attention mechanism as shown (image source)

Another approach to leveraging pre-trained language models for multi-modal tasks is to directly fuse visual information into the layers of a language model decoder using a cross-attention mechanism instead of using images as additional prefixes to the language model. Models such as VisualGPT, VC-GPT, and Flamingo use this pre-training strategy and are trained on image captioning and visual question-answering tasks. The main goal of such models is to balance the mixture of text generation capacity and visual information efficiently, which is highly important in the absence of large multi-modal datasets.

Models such as VisualGPT use a visual encoder to embed images and feed the visual embeddings to the cross-attention layers of a pre-trained language decoder module to generate plausible captions. A more recent work, FIBER, inserts cross-attention layers with a gating mechanism into both vision and language backbones, for more efficient multi-modal fusing and enables various other downstream tasks, such as image-text retrieval and open vocabulary object detection.

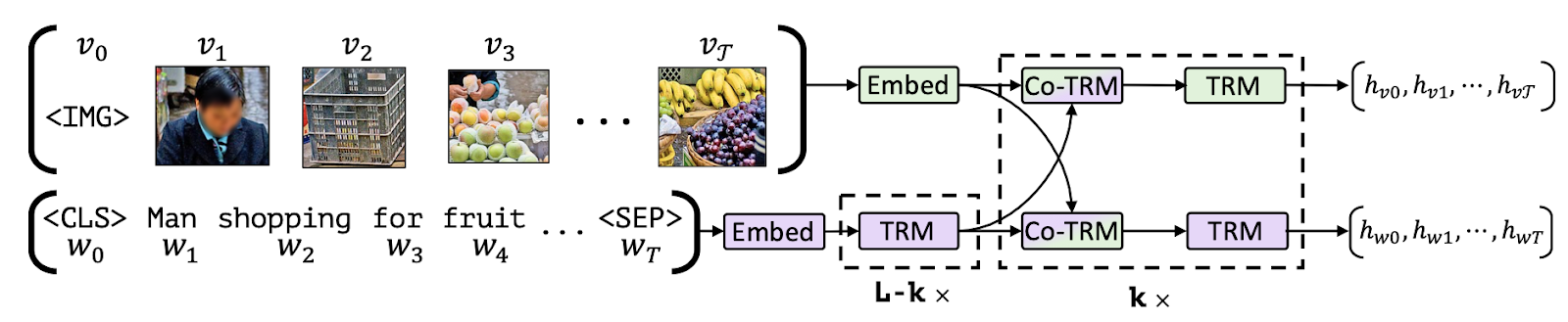

4) Masked-Language Modeling / Image-Text Matching

Another line of vision-language models uses a combination of Masked-Language Modeling (MLM) and Image-Text Matching (ITM) objectives to align specific parts of images with text and enable various downstream tasks such as visual question answering, visual commonsense reasoning, text-based image retrieval, and text-guided object detection. Models that follow this pre-training setup include VisualBERT, FLAVA, ViLBERT, LXMERT and BridgeTower.

Aligning parts of images with text (image source)

Let’s break down what MLM and ITM objectives mean. Given a partially masked caption, the MLM objective is to predict the masked words based on the corresponding image. Note that the MLM objective requires either using a richly annotated multi-modal dataset with bounding boxes or using an object detection model to generate object region proposals for parts of the input text.

For the ITM objective, given an image and caption pair, the task is to predict whether the caption matches the image or not. The negative samples are usually randomly sampled from the dataset itself. The MLM and ITM objectives are often combined during the pre-training of multi-modal models. For instance, VisualBERT proposes a BERT-like architecture that uses a pre-trained object detection model, Faster-RCNN, to detect objects. This model uses a combination of the MLM and ITM objectives during pre-training to implicitly align elements of an input text and regions in an associated input image with self-attention.

Another work, FLAVA, consists of an image encoder, a text encoder, and a multi-modal encoder to fuse and align the image and text representations for multi-modal reasoning, all of which are based on transformers. In order to achieve this, FLAVA uses a variety of pre-training objectives: MLM, ITM, as well as Masked-Image Modeling (MIM), and contrastive learning.

5) No Training

Finally, various optimization strategies aim to bridge image and text representations using the pre-trained image and text models or adapt pre-trained multi-modal models to new downstream tasks without additional training.

For example, MaGiC proposes iterative optimization through a pre-trained autoregressive language model to generate a caption for the input image. To do this, MaGiC computes a CLIP-based “Magic score” using CLIP embeddings of the generated tokens and the input image.

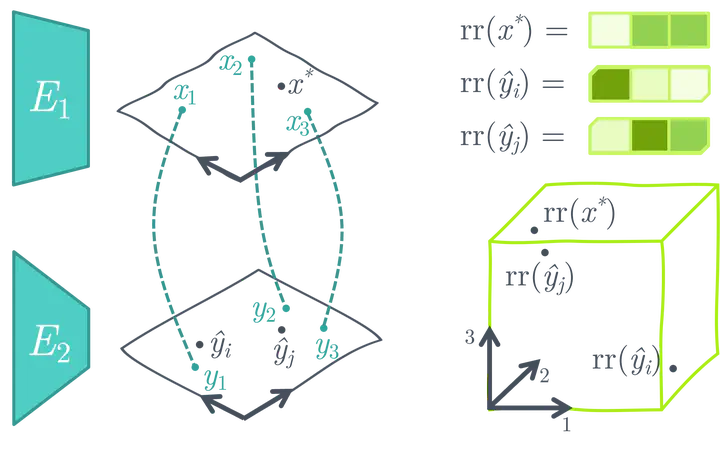

Crafting a similarity search space using pre-trained, frozen unimodal image and text encoders (image source)

ASIF proposes a simple method to turn pre-trained uni-modal image and text models into a multi-modal model for image captioning using a relatively small multi-modal dataset without additional training. The key intuition behind ASIF is that captions of similar images are also similar to each other. Hence we can perform a similarity-based search by crafting a relative representation space using a small dataset of ground-truth multi-modal pairs.

Datasets

Vision-language models are typically trained on large image and text datasets with different structures based on the pre-training objective. After they are pre-trained, they are further fine-tuned on various downstream tasks using task-specific datasets. This section provides an overview of some popular pre-training and downstream datasets used for training and evaluating vision-language models.

Pre-training datasets

Vision-language models are typically pre-trained on large multi-modal datasets harvested from the web in the form of matching image/video and text pairs. The text data in these datasets can be human-generated captions, automatically generated captions, image metadata, or simple object labels. Some examples of such large datasets are PMD and LAION-5B. The PMD dataset combines multiple smaller datasets such as the Flickr30K, COCO, and Conceptual Captions datasets. The COCO detection and image captioning (>330K images) datasets consist of image instances paired with the text labels of the objects each image contains, and natural sentence descriptions, respectively. The Conceptual Captions (> 3.3M images) and Flickr30K (> 31K images) datasets are scraped from the web along with their captions - free-form sentences describing the image.

Even image-text datasets consisting solely of human-generated captions, such as Flickr30K, are inherently noisy as users only sometimes write descriptive or reflective captions for their images. To overcome this issue, datasets such as the LAION-5B dataset leverage CLIP or other pre-trained multi-modal models to filter noisy data and create high-quality multi-modal datasets. Furthermore, some vision-language models, such as ALIGN, propose further preprocessing steps and create their own high-quality datasets. Other vision-language datasets, such as the LSVTD and WebVid datasets, consist of video and text modalities, although at a smaller scale.

Downstream datasets

Pre-trained vision-language models are often trained on various downstream tasks such as visual question-answering, text-guided object detection, text-guided image inpainting, multi-modal classification, and various stand-alone NLP and computer vision tasks.

Models fine-tuned on the question-answering downstream task, such as ViLT and GLIP, most commonly use the VQA (visual question-answering), VQA v2, NLVR2, OKVQA, TextVQA, TextCaps and VizWiz datasets. These datasets typically contain images paired with multiple open-ended questions and answers. Furthermore, datasets such as VizWiz and TextCaps can also be used for image segmentation and object localization downstream tasks. Some other interesting multi-modal downstream datasets are Hateful Memes for multi-modal classification, SNLI-VE for visual entailment prediction, and Winoground for visio-linguistic compositional reasoning.

Note that vision-language models are used for various classical NLP and computer vision tasks such as text or image classification and typically use uni-modal datasets (SST2, ImageNet-1k, for example) for such downstream tasks. In addition, datasets such as COCO and Conceptual Captions are commonly used both in the pre-training of models and also for the caption generation downstream task.

Supporting Vision-Language Models in 🤗 Transformers

Using Hugging Face Transformers, you can easily download, run and fine-tune various pre-trained vision-language models or mix and match pre-trained vision and language models to create your own recipe. Some of the vision-language models supported by 🤗 Transformers are:

- CLIP

- FLAVA

- GIT

- BridgeTower

- GroupViT

- BLIP

- OWL-ViT

- CLIPSeg

- X-CLIP

- VisualBERT

- ViLT

- LiT (an instance of the

VisionTextDualEncoder) - TrOCR (an instance of the

VisionEncoderDecoderModel) VisionTextDualEncoderVisionEncoderDecoderModel

While models such as CLIP, FLAVA, BridgeTower, BLIP, LiT and VisionEncoderDecoder models provide joint image-text embeddings that can be used for downstream tasks such as zero-shot image classification, other models are trained on interesting downstream tasks. In addition, FLAVA is trained with both unimodal and multi-modal pre-training objectives and can be used for both unimodal vision or language tasks and multi-modal tasks.

For example, OWL-ViT enables zero-shot / text-guided and one-shot / image-guided object detection, CLIPSeg and GroupViT enable text and image-guided image segmentation, and VisualBERT, GIT and ViLT enable visual question answering as well as various other tasks. X-CLIP is a multi-modal model trained with video and text modalities and enables zero-shot video classification similar to CLIP’s zero-shot image classification capabilities.

Unlike other models, the VisionEncoderDecoderModel is a cookie-cutter model that can be used to initialize an image-to-text model with any pre-trained Transformer-based vision model as the encoder (e.g. ViT, BEiT, DeiT, Swin) and any pre-trained language model as the decoder (e.g. RoBERTa, GPT2, BERT, DistilBERT). In fact, TrOCR is an instance of this cookie-cutter class.

Let’s go ahead and experiment with some of these models. We will use ViLT for visual question answering and CLIPSeg for zero-shot image segmentation. First, let’s install 🤗Transformers: pip install transformers.

ViLT for VQA

Let’s start with ViLT and download a model pre-trained on the VQA dataset. We can do this by simply initializing the corresponding model class and calling the from_pretrained() method to download our desired checkpoint.

from transformers import ViltProcessor, ViltForQuestionAnswering

model = ViltForQuestionAnswering.from_pretrained("dandelin/vilt-b32-finetuned-vqa")

Next, we will download a random image of two cats and preprocess both the image and our query question to transform them to the input format expected by the model. To do this, we can conveniently use the corresponding preprocessor class (ViltProcessor) and initialize it with the preprocessing configuration of the corresponding checkpoint.

import requests

from PIL import Image

processor = ViltProcessor.from_pretrained("dandelin/vilt-b32-finetuned-vqa")

# download an input image

url = "http://images.cocodataset.org/val2017/000000039769.jpg"

image = Image.open(requests.get(url, stream=True).raw)

text = "How many cats are there?"

# prepare inputs

inputs = processor(image, text, return_tensors="pt")

Finally, we can perform inference using the preprocessed image and question as input and print the predicted answer. However, an important point to keep in mind is to make sure your text input resembles the question templates used in the training setup. You can refer to the paper and the dataset to learn how the questions are formed.

import torch

# forward pass

with torch.no_grad():

outputs = model(**inputs)

logits = outputs.logits

idx = logits.argmax(-1).item()

print("Predicted answer:", model.config.id2label[idx])

Straight-forward, right? Let’s do another demonstration with CLIPSeg and see how we can perform zero-shot image segmentation with a few lines of code.

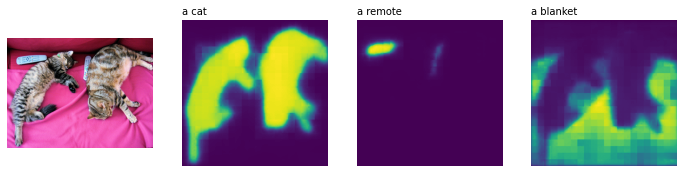

CLIPSeg for zero-shot image segmentation

We will start by initializing CLIPSegForImageSegmentation and its corresponding preprocessing class and load our pre-trained model.

from transformers import CLIPSegProcessor, CLIPSegForImageSegmentation

processor = CLIPSegProcessor.from_pretrained("CIDAS/clipseg-rd64-refined")

model = CLIPSegForImageSegmentation.from_pretrained("CIDAS/clipseg-rd64-refined")

Next, we will use the same input image and query the model with the text descriptions of all objects we want to segment. Similar to other preprocessors, CLIPSegProcessor transforms the inputs to the format expected by the model. As we want to segment multiple objects, we input the same image for each text description separately.

from PIL import Image

import requests

url = "http://images.cocodataset.org/val2017/000000039769.jpg"

image = Image.open(requests.get(url, stream=True).raw)

texts = ["a cat", "a remote", "a blanket"]

inputs = processor(text=texts, images=[image] * len(texts), padding=True, return_tensors="pt")

Similar to ViLT, it’s important to refer to the original work to see what kind of text prompts are used to train the model in order to get the best performance during inference. While CLIPSeg is trained on simple object descriptions (e.g., “a car”), its CLIP backbone is pre-trained on engineered text templates (e.g., “an image of a car”, “a photo of a car”) and kept frozen during training. Once the inputs are preprocessed, we can perform inference to get a binary segmentation map of shape (height, width) for each text query.

import torch

with torch.no_grad():

outputs = model(**inputs)

logits = outputs.logits

print(logits.shape)

>>> torch.Size([3, 352, 352])

Let’s visualize the results to see how well CLIPSeg performed (code is adapted from this post).

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

logits = logits.unsqueeze(1)

_, ax = plt.subplots(1, len(texts) + 1, figsize=(3*(len(texts) + 1), 12))

[a.axis('off') for a in ax.flatten()]

ax[0].imshow(image)

[ax[i+1].imshow(torch.sigmoid(logits[i][0])) for i in range(len(texts))];

[ax[i+1].text(0, -15, prompt) for i, prompt in enumerate(texts)]

Amazing, isn’t it?

Vision-language models enable a plethora of useful and interesting use cases that go beyond just VQA and zero-shot segmentation. We encourage you to try out the different use cases supported by the models mentioned in this section. For sample code, refer to the respective documentation of the models.

Emerging Areas of Research

With the massive advances in vision-language models, we see the emergence of new downstream tasks and application areas, such as medicine and robotics. For example, vision-language models are increasingly getting adopted for medical use cases, resulting in works such as Clinical-BERT for medical diagnosis and report generation from radiographs and MedFuseNet for visual question answering in the medical domain.

We also see a massive surge of works that leverage joint vision-language representations for image manipulation (e.g., StyleCLIP, StyleMC, DiffusionCLIP), text-based video retrieval (e.g., X-CLIP) and manipulation (e.g., Text2Live) and 3D shape and texture manipulation (e.g., AvatarCLIP, CLIP-NeRF, Latent3D, CLIPFace, Text2Mesh). In a similar line of work, MVT proposes a joint 3D scene-text representation model, which can be used for various downstream tasks such as 3D scene completion.

While robotics research hasn’t leveraged vision-language models on a wide scale yet, we see works such as CLIPort leveraging joint vision-language representations for end-to-end imitation learning and reporting large improvements over previous SOTA. We also see that large language models are increasingly getting adopted in robotics tasks such as common sense reasoning, navigation, and task planning. For example, ProgPrompt proposes a framework to generate situated robot task plans using large language models (LLMs). Similarly, SayCan uses LLMs to select the most plausible actions given a visual description of the environment and available objects. While these advances are impressive, robotics research is still confined to limited sets of environments and objects due to the limitation of object detection datasets. With the emergence of open-vocabulary object detection models such as OWL-ViT and GLIP, we can expect a tighter integration of multi-modal models with robotic navigation, reasoning, manipulation, and task-planning frameworks.

Conclusion

There have been incredible advances in multi-modal models in recent years, with vision-language models making the most significant leap in performance and the variety of use cases and applications. In this blog, we talked about the latest advancements in vision-language models, as well as what multi-modal datasets are available and which pre-training strategies we can use to train and fine-tune such models. We also showed how these models are integrated into 🤗 Transformers and how you can use them to perform various tasks with a few lines of code.

We are continuing to integrate the most impactful computer vision and multi-modal models and would love to hear back from you. To stay up to date with the latest news in multi-modal research, you can follow us on Twitter: @adirik, @NielsRogge, @apsdehal, @a_e_roberts, @RisingSayak, and @huggingface.

Acknowledgements: We thank Amanpreet Singh and Amy Roberts for their rigorous reviews. Also, thanks to Niels Rogge, Younes Belkada, and Suraj Patil, among many others at Hugging Face, who laid out the foundations for increasing the use of multi-modal models from Transformers.